The relationship between art and design is often misunderstood, and although a design outcome can be artful, the process behind it is altogether very different. Toptalauthors are vetted experts in their fields and write on topics in which they have demonstrated experience. All of our content is peer reviewed and validated by Toptal experts in the same field.

The relationship between art and design is often misunderstood, and although a design outcome can be artful, the process behind it is altogether very different. Toptalauthors are vetted experts in their fields and write on topics in which they have demonstrated experience. All of our content is peer reviewed and validated by Toptal experts in the same field.

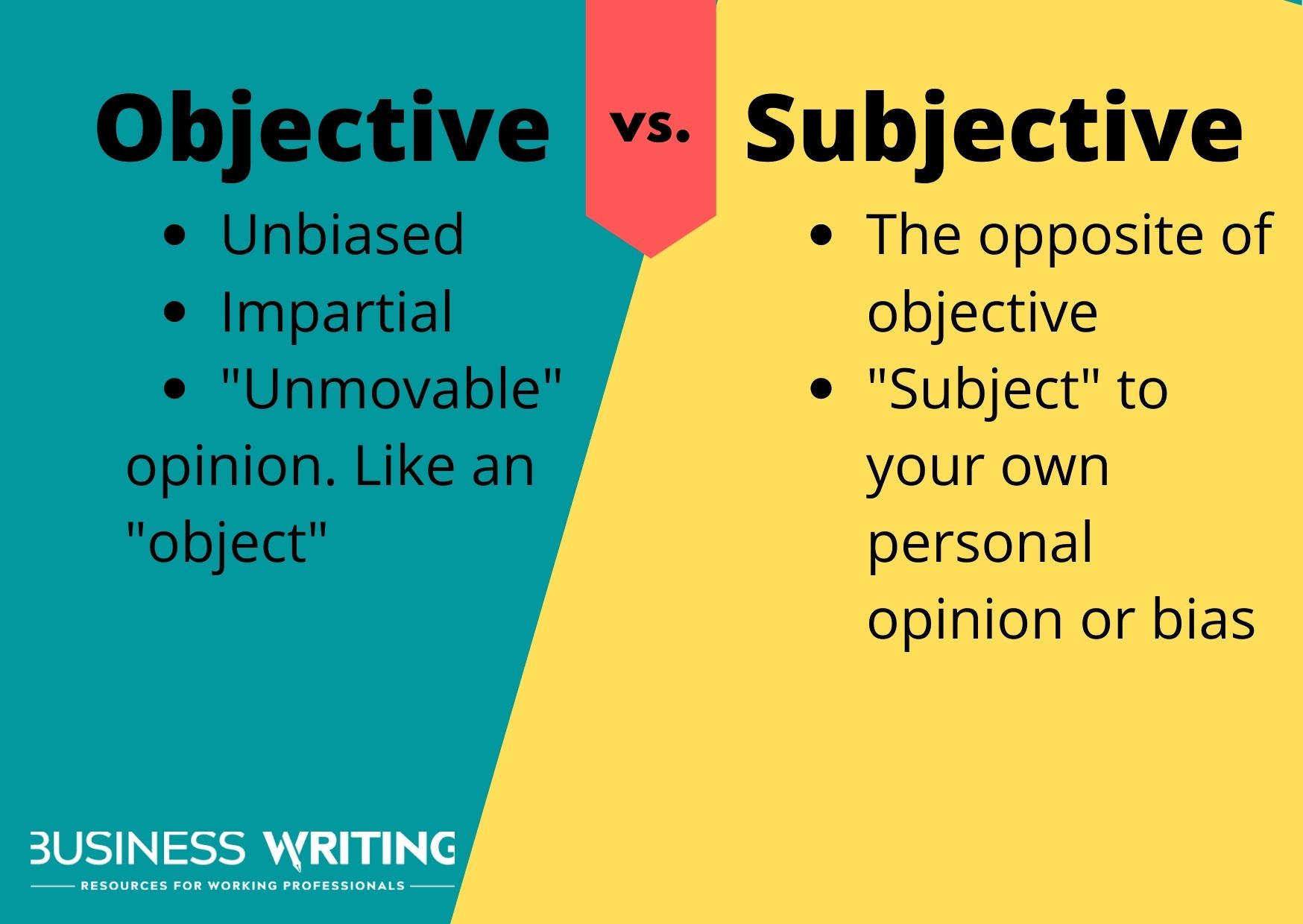

Product design is both an art and a science. To create successful, usable products that delight customers, designers must balance objective factors like ergonomics and usability with more subjective aspects like aesthetics and emotional appeal This article explores key differences between subjective and objective product design and strategies to strike an optimal balance

Defining Subjective vs Objective Design

Objective design focuses on pragmatic, functional factors that can be concretely measured and evaluated. It prioritizes goals like:

- Usability

- Accessibility

- Technical performance

- Durability

Objective design follows established principles like anthropometrics, heuristics, and standardized norms. It aims to create products optimized for practical use based on factual data.

In contrast, subjective design centers on intangible aspects like:

- Aesthetics

- Emotional impact

- Cultural meanings

- Individual preferences

Subjective design taps into human psychology to evoke certain perceptions, feelings, and associations. It expresses style, personality, and artistry.

Both objective and subjective considerations are integral to excellent product design. Usability without emotional resonance feels hollow. Beauty without function lacks purpose. The most successful products fuse both.

Key Objective Design Criteria

Several core criteria provide a framework for objectively evaluating product designs,

Ergonomics and Anthropometrics

Ergonomics focuses on optimizing products for human use. Anthropometrics provides data on the capabilities and limitations of the human body.

Product designers rely on anthropometric databases documenting averages and ranges for measurements like:

- Height

- Arm reach

- Grip diameter

- Strength

- Dexterity

This data ensures products physically accommodate target users. For example, door handles are installed at heights suited to most people’s arm length. Seat dimensions fit the 95th percentile of buttock-knee length.

Of course, ergonomic suitability depends partly on context. A school chair must accommodate a different range of users than an office chair.

Usability and Accessibility

Usability testing provides objective metrics like:

- Task success rate – % of users who can complete key tasks

- Time on task – How long users take to complete tasks

- Error count – Number of errors made during tasks

Other usability benchmarks include satisfaction scores and click counts.

Accessibility standards outline objective design criteria to accommodate users with disabilities. These include:

- Alt text for images

- Closed captioning

- Keyboard navigation

- Color contrast

- Font size

Performance and Durability

Technical performance and durability have objective design implications. Materials must withstand expected use cycles and stresses. Electronics must deliver processing speeds, battery life, and connectivity to fulfill functional needs.

Industrial designers conduct durability testing by simulating conditions like:

- Drop impact

- Thermal cycling

- Exposure to moisture

- Abrasion

- UV radiation

Performance is benchmarked through metrics like computing power and battery duration.

Key Subjective Design Factors

Subjective design centers on shaping user emotions and perceptions. Key strategies include:

Appealing Aesthetics

Visual presentation can spark joy or disappointment before products are even used. For example, slick aesthetics signal high quality. Rounded edges feel friendly and approachable.

Subjective reactions depend partly on design styles and trends. Skeuomorphic designs mimicking real-world objects can feel nostalgic yet outdated compared to sleek, modern flat aesthetics.

Meaningful Metaphors

Metaphors conjure up associations that shape perceptions. For example, bird sounds and imagery on a nature app connect it to ideas like freedom and lightness.

Cultural differences make metaphors subjective. Colors have varied symbolic meanings. Icons like checkmarks aren’t universally understood.

Brand Messaging

Branding communicates the personality and values of a product. For example, outdoorsy imagery could reinforce the durability of a watch. Sleek minimalism might convey a tech company’s modernity.

Brand identity triggers subjective impressions that influence purchase decisions. Successful branding is cohesive yet distinctive.

Emotional Design Principles

Emotional design techniques help products connect with users on a deeper level. For example:

-

Nostalgic design plays to fond memories and retro sensibilities by using themes, motifs, and styles from the past. This creates warm, familiar feelings.

-

Minimalism pursues simplicity and clarity to evoke calmness and focus. Open space and natural textures promote relaxation.

-

Vibrant color palettes capture attention and impart energy. Bright accent colors enliven more neutral backgrounds.

-

Organic shapes with rounded edges or natural irregularities feel inherently more human and friendly than rigid geometric forms.

User Psychology

Design choices can tap into psychological tendencies. For example:

- Decoy pricing makes higher-priced options seem more reasonable in comparison.

- Priming people with positive stimuli promotes goodwill towards a brand.

- Following the Gestalt principles of continuity, closure, and symmetry make interfaces feel orderly and pleasing.

Leveraging quirks of human psychology encourages subjective reactions that benefit the product.

Achieving the Optimal Balance

The most successful product design holistically blends objective and subjective elements. However, strategies for striking the right balance vary.

Considerations include:

-

Product purpose – A medical device demands greater focus on objective criteria than a consumer gift.

-

User needs – Designing for utility-driven expert users versus choice-driven first-time buyers entails different approaches.

-

Business goals – Building brand recognition may warrant more subjective design than streamlining manufacturing costs.

-

Audience demographics – Younger users often prioritize style, while older ones emphasize usability. Cultural context is key.

-

Environment – Products used in distracting public settings face different demands than ones used in quiet private settings.

-

Available resources – Time, budget, and team skills constrain feasible design scopes.

While subjective design seems frivolous, emotional connection is what transforms commodities into beloved products. However, style must not undermine function.

User research, conceptual modeling, prototyping, and usability testing help align subjective design goals with objective user needs. Testing both functional performance and emotional resonance reveals the right proportions.

For example, eye-catching colors or animations that initially delighted users often prove annoying after prolonged use. Personas and storyboards ensure aesthetic choices align with user lifestyles.

Best Practices for Balance

Some tips for harmonizing style and utility include:

-

Adopt objective design methods first to establish usability. Then refine aesthetics and branding.

-

Set measurable benchmarks for both objective metrics and subjective perceptions.

-

Validate conceptual ideas through prototyping to identify potential disconnects between looks and function early.

-

Conduct generative research to uncover users’ unspoken psychological needs.

-

Factor in subjective perceptions of beauty and quality in analytical selection criteria alongside objective performance data.

-

Align visual styling with functional priorities, like highlighting clickable elements.

-

Treat compliance with usability heuristics and accessibility standards as prerequisites rather than optional extras.

-

Design structural and technical elements to accommodate potential future styling flexibility.

-

Develop a visual library of interface patterns coded by factors like emotion, energetics, and usability to inform aesthetic choices.

-

Leverage tools like heatmaps, A/B testing, biometric measurements, and surveys to quantify emotional design impacts.

With careful balancing, products can deliver both beauty and utility in a captivating user experience. Objective and subjective design are best seen as complementary rather than opposing approaches. By artfully blending both, product designers can maximize appeal, enjoyment, and adoption.

ByBronwen Rees

Bronwen is a designer from London with experience in both brand and digital design. Her passion lies in learning and evolving her skills.

Design is complicated. Some types of design are more subjective, “artful”—some are more utilitarian and follow more rigid rules. What process do we follow to create digital design solutions? Is it an inevitable conclusion of mechanically applying objective principles to a problem (functional design), or is it the organic result of more subjective decision making?

The relationship between art and design is often misunderstood, and although a design outcome can be artful, the process behind it is altogether very different.

An artist aims to aesthetically express personal ideas or feelings through a particular medium. Art is valued for its originality and ability to explore alternative representations of an appearance, people, or things. With art, you either get it or you don’t—and that’s fine.

Design, however, is the result of a number of decisions made by one or more designers trying to solve a specific problem relative to a user; it is then evaluated simply by how successful it is at solving that problem. If unsuccessful, then the design has failed.

The Design of Everyday Things is a fantastic book by cognitive scientist and usability engineer Donald Norman about how design is the communication between an object and the user, and how to make the experience of using an object pleasurable.

One area of exploration within the book is how often people will naturally blame themselves for being unable to use an object as intended, although it is never the fault of the user. It makes the case for how the design of an object should fulfill a user’s objective, be intuitive to use, and not require training. If it does, then the object’s design has failed.

But what has this got to do with objectivity in design? Let’s look at how we term objectivity and its role in the design process.

Understanding the definitions will help differentiate between something being objective or subjective:

- Objective (adj) – not influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions

- Subjective (adj) – influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions

Using these definitions, we may surmise that design is primarily an objective process. To become successful as a designer, it is advisable we follow an objective process in a project’s initial phase, rather than being influenced by emotions, “taste,” hypotheses, and unfounded assumptions.

Nevertheless, all good intentions aside, when it comes to designing for clients or other people, the design process can be misunderstood and objectivity excluded from the conversation. Instead, to judge the success of a design outcome, we fall back on our aesthetic sensibility and our emotions, and are influenced by how we “feel” about the design.

The problem is, our emotions and how we feel are unpredictable, uncertain, and very complicated. They are subjective. Our judgment is greatly affected if we don’t understand the relationship between the objective approach in design and the influence general aesthetics could have on our emotions.

When it comes to design, as an industry, ours is afflicted with an abundance of self-deception. We each believe we are doing more than just painting by numbers.

Good design is objective because it just works.

It works because the initial design application follows a system or framework—every subsequent design decision has a reason, and every styled element can be explained. Having set up a strong foundation, it is also a result of well-considered subjectivity.

Human emotion is critical when deciding whether to engage with a website or product; therefore, the aesthetics are equally important.

I consider myself to be an objective person and I expect that you do too. Objectivity is easier, especially when learning a new subject. It’s easier to understand all the objective principles within that subject and understand the truths; by knowing the facts, it makes it easier to decipher the subject. This is how we initially approach design.

There are basic systems and frameworks—design truths—that can be applied to design to ensure that our approach is as objective as it can be. Some examples of these are:

User research focuses on understanding user behaviors, needs, and motivations through observation techniques, task analysis, and other feedback methodologies. It is “the process of understanding the impact of design on an audience” (Mike Kuniaysky).

The purpose of user research is to help us design objectively with the end user in mind. It is research that prevents us from designing for ourselves and influencing the design with our subjective opinions. Instead, user research tells us who the person is, in what context they’ll use this product or service, and what they need from us.

Design is most effective when executed with knowledge of human psychology. Understanding how the mind reacts to visual stimuli allows the crafting of an objective design—without psychology, you are just guessing. Psychology itself is a massive subject, but that doesn’t mean you need a Ph.D. to use it in your design. There are simple psychological principles you can use to improve the effectiveness of your design without knowing the theory behind it.

Using clear and [effective design best practices] (https://www.toptal.com/designers/ui/principles-of-design), conventions, and standards as guides, we can use proven formulas for better, more objective design. UX design best practices both aid the usability of our design as well as the aesthetic value. Furthermore, being able to refer back to these conventions and standards when presenting or discussing your design can further help you establish yourself as knowledgeable, with justified, objective reasons for your design choices.

All businesses have goals in mind when briefing a project, and it’s the job of the designer to accomplish these. It may be necessary for them to be dissected and adjusted to align with the needs of the user, but ultimately the business will set the objectives of the project. It may seem to be common sense to mention this, but it’s remarkable how many times important business objectives can be overlooked, especially when they may not align with the users’ needs.

A designer who has a clear idea of what needs to be achieved is far more potent than one who is simply trying to make something look pretty.

Finding the Balance Between Objective and Subjective

Design systems and frameworks may seem like objective things, until the moment we have to actually use them. It seemed objectively obvious to give users search suggestions, but why not just allow them to search as they please and then filter the results? What made one a better choice than the other? The answer has less to do with an absolute rule and more to do with subjective experience.

The design of anything involves making a lot of decisions. You have to decide what the thing will do and how it will do it. Decisions on what features to include and, more importantly, what not to include have to be made. From the moment the design process begins to the moment you stop, decisions are being made. While these decisions may be objectively founded with the help of systems and frameworks, what decisions we take are ultimately our subjective choice.

Design systems and frameworks are there to provide context—to help in the decision process. Based on vast amounts of previous experience, they offer well-proven templates and guidelines to help reduce the limitless options to just a sensible few. However, just because there are guidelines, it doesn’t mean there is no flexibility.

Architecture has a fundamental, unchangeable guideline—the laws of physics. For example, take Federation Square in Melbourne, Australia; there has always been a lot of opinion about this building, and not everyone has always loved it.

There were five very different designs presented to the board when Federation Square was first proposed, all from different firms. While each idea was unique in concept, all of them had one key thing in common: physics.

There is always going to be lots of decisions to be made within the scope of a project. The earliest and more important decisions will be informed by the objective principles; the goals of the project, the user and psychological research, and the best practices, standards, and conventions. A roadmap is then provided to help with the decisions that will come after that, but they will also be informed by your own experiences and observations.

When it comes to design, if someone challenges your design outcomes with an aesthetic or emotional response, they need to be reminded that design decisions are based on objective reasoning.

Designers are highly disciplined professionals. They have the ability to perceive and interpret the grey areas and turn them into black and white—and they use both objectivity and subjectivity to create greater user experiences.

But most importantly, they create designs that just work.

What EXACTLY is Product Design?

What is the difference between objective and subjective design?

As a refresher, objective design is not influenced by personal feelings or opinions, whereas subjective design is based on personal feelings or opinions. Objective design means the product must be based on facts, data and how real people learn or use things. It can’t just be about “making something look pretty.”

What is the difference between subjective and objective?

Since there’s so much confusion, let’s start by clarifying the difference between “subjective” and “objective.” In a design context, the difference between “subjective” and “objective” depends on whether the end-result is based on opinions or facts. Subjective: Based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions.

Is design subjective?

Regardless of how ugly a design may be, one cannot argue that design is subjective. Design exists to solve real problems, which inherently makes it objective. Rather than concluding that design is subjective, perhaps we should be more concerned with “how” objective we are with design.

What is subjective product design?

You can use subjective product design to help evoke a certain emotion from the viewer, depending on your desired outcome. For example, you might add bright colors or bold shapes to encourage excitement. This could be useful in the design of an advertisement or a children’s toy.