“Make sure you practice writing dialogue!” her mother instructed. “Because dialogue is one of the most effective tools a writer has to bring characters to life.” Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently

Dialogue brings fiction to life. It reveals character drives the story and keeps readers hooked. Mastering the art of writing authentic crisp dialogue is essential for novelists and short story writers.

But writing great dialogue is not easy. Stilted, awkward dialogue is a common pitfall for writers So how do you write dialogue that flows smoothly, adds depth and brings out the voices of characters?

Here is a comprehensive guide to writing captivating dialogue for fiction:

Give Each Character Their Own Unique Voice

Every character should speak in a way that is distinctive and true to who they are, To achieve this

-

Consider background – How might upbringing, education, social class, influence how a character speaks? An aristocratic character will speak differently than a rural farmhand.

-

Factor in age – Young characters use different vocabulary and sentence constructions than older ones. Pay attention to age-appropriate dialogue.

-

Define personality – An introvert speaks differently than an extrovert. Reflect personality traits through dialogue quirks.

-

Consider profession – Professional jargon can shape dialogue. A doctor will talk differently than a soldier or teacher.

-

Unique word choices – Certain words and phrases may be typical for a character. Bring out uniqueness.

-

Idiosyncrasies – Give each character verbal eccentricities and quirks that identify them immediately.

Making each voice distinct avoids confusing similar characters. Listen to conversations around you and take note of how real people speak.

Avoid Writing Dialogue Just for Exposition Dumps

Having characters explain facts just to convey information to the reader is an amateur mistake. For example:

“As you know, Amy, our town Elmwood was settled in 1873 and has a population of 5,000 people.”

This is boring, stilted dialogue only meant to state facts. Use exposition subtly and try to convey background organically through context. Reveal details through implications in dialogue, not direct statements.

Use Dialogue to Reveal Inner Conflicts

Well-written dialogue often hints at deeper emotions and conflicts. Maybe your character says one thing but implies something else. This creates complexity. For example:

“I’m completely fine with you going to the movie without me. I’ll just stay in and read.”

This surfaces underlying hurt or resentment. Dialogue works well to disclose emotions that characters prefer to keep hidden. Use body language as cues too.

Make Dialogue Reveal Character Agendas and Motivations

As the story progresses, well-crafted dialogue reveals what characters deeply desire, what they long for, their motivations and secret agendas.

For example, seemingly innocuous statements about the future can signal ambition:

“After I leave this dead-end town, I’m going to be so rich and powerful, just you watch.”

This reveals the character’s inner drive for success and high status. Their agenda emerges through such statements.

Use Dialogue Tags Wisely

“Said” is fine for most dialogue tags. Avoid fancy tags like “uttered”, “voiced”, “expressed” etc. These distract. Only use expressive tags when they add value:

“I’m afraid we need to talk,” she sighed.

“You stole from me!” he thundered.

Too many tags become repetitive. Use action to indicate who is speaking:

Josh slammed his fist on the table. “I’ve had enough of your lies!”

Write Dialogue, Not Monologues

Characters who speak for too long sound unnatural. Limit speeches to 2-3 lines at most. Back-and-forth exchanges work better.

Rather than a soliloquy, break it up:

“You don’t understand why I did it. After years of nobody listening and turning their backs, I just had to act. I had no choice but to…”

“No choice but to destroy our livelihoods? Don’t try to justify what you did!” she retorted.

Keep things tight. Long speeches slow down pace.

Use Dialogue to Build Tension

Dialogue during tense scenes can ratchet up drama and conflict. Use short, sharp exchanges to accentuate the character’s frayed emotional states.

“Get away from me!”

“No, we’re working this out.”

“I said get away!”

“No! Tell me why you…”

“Just stop! Get away or I’ll…”

Quick back-and-forth heightens tension. Long-winded replies release all the built-up tension.

Advance the Plot Through Dialogue

Dialogue provides opportunities to subtly move the story forward. Information vital to the plot can surface naturally during a conversation.

For example, one character’s casual remark about bumping into someone seeds a future plot twist. Dialogue can pave the way for plot developments.

Don’t Use Dialogue to Force Feed Backstory

Encapsulating backstory through long recollections in dialogue rarely works. Find subtler ways to give background rather than monologues like:

“Let me tell you about my childhood…”

Instead, drop hints and clues to the past through exchanges:

“You’re just like your father!”

Bits of history can emerge this way without stopping the story dead to explain everything.

Write Dialogue and Subtext That Contradicts

What’s left unsaid in dialogue often matters more than what’s said. Have an unspoken subtext beneath the surface words:

“I’m happy you’re going away for weeks. I’ll enjoy the time alone.”

This hints that maybe they want to end the relationship but don’t say it outright. Create tension between subtext and spoken text.

Don’t Use Accents and Dialects Excessively

A light sprinkle of dialect gives characters an authentic voice. But heavy use of accented spellings and apostrophes is taxing to read:

“Whar’ ya goin’ with that there wagon?”

Prefer hints of dialect over making it hard to decipher:

“Where you headed with that wagon?” he asked in a heavy rural accent.

Use dialect sparingly for light flavor.

Make Dialogue Feel Realistic

Real conversations have messy cadences and flows. They meander and get derailed easily. Recreate that natural spontaneity:

“Do you think it will rain today? What was the weather app saying? By the way, did you pick up the groceries? I forgot the milk again…”

Long blocks of perfect grammar sound artificial. Write dialogue like people actually talk.

Avoid Long Speeches for Info Dumping

Characters who speak for too long expounding on facts sound unrealistic. Avoid big blocks of endless dialogue as fact delivery:

“As you know, sis, our great nation Spain has a proud history dating back to 218 B.C…”

Clunky and boring. Break it up. Reveal facts more organically.

Use Dialogue to Show Power Dynamics

Status and power structures influence how characters speak to each other. Show power relations through dialogue cues:

A boss barking orders shows authority over an assistant. Or a child deferentially addressing a parent versus joking with friends.

Show status through deference, formality, tone etc. This helps establish relationships.

Pick Up the Pace with Crisp Dialogue

During action sequences, rapid-fire dialogue adds pace:

“Freeze!”

“Out of my way!”

“Stop him!”

Trim the fat. Avoid long monologues that stall momentum. Deliver the essence.

Let Characters Interrupt Each Other

People interrupt all the time in real conversations. Use interruptions to build realism:

“If you’d just listen for a second…”

“No, it’s my turn to talk!”

Read your dialogue aloud. Does it sound natural? Discussing with others helps identify gaps.

In conclusion, excellent dialogue comes from understanding characters intimately. Crafting authentic, memorable voices takes effort and close attention to how real people speak and interact. Use dialogue not just to convey information, but to reveal deeper character goals and conflicts. Great dialogue propels the story, builds tension and brings fiction to life.

What is dialogue, and what is its purpose?

Dialogue is what the characters in your short story, poem, novel, play, screenplay, personal essay—any kind of creative writing where characters speak—say out loud.

For a lot of writers, writing dialogue is the most fun part of writing. It’s your opportunity to let your characters’ motivations, flaws, knowledge, fears, and personality quirks come to life. By writing dialogue, you’re giving your characters their own voices, fleshing them out from concepts into three-dimensional characters. And it’s your opportunity to break grammatical rules and express things more creatively. Read these lines of dialogue:

- “NoOoOoOoO!” Maddie yodeled as her older sister tried to pry her hands from the merry-go-round’s bars.

- “So I says, ‘You wanna play rough? C’mere, I’ll show you playin’ rough!’”

- “Get out!” she shouted, playfully swatting at his arm. “You’re kidding me, right? We couldn’t have won . . . ”

Dialogue has multiple purposes. One of them is to characterize your characters. Read the examples above again, and think about who each of those characters are. You learn a lot about somebody’s mindset, background, comfort in their current situation, emotional state, and level of expertise from how they speak.

Another purpose dialogue has is exposition, or background information. You can’t give readers all the exposition they need to understand a story’s plot up-front. One effective way to give readers information about the plot and context is to supplement narrative exposition with dialogue. For example, the protagonist might learn about an upcoming music contest by overhearing their coworkers’ conversation about it, or an intrepid adventurer might be told of her destiny during an important meeting with the town mystic. Later on in the story, your music-loving protagonist might express his fears of looking foolish onstage to his girlfriend, and your intrepid adventurer might have a heart-to-heart with the dragon she was sent to slay and find out the truth about her society’s cultural norms.

Dialogue also makes your writing feel more immersive. It breaks up long prose passages and gives your reader something to “hear” other than your narrator’s voice. Often, writers use dialogue to also show how characters relate to each other, their setting, and the plot they’re moving through.

It can communicate subtext, like showing class differences between characters through the vocabulary they use or hinting at a shared history between them. Sometimes, a narrator’s description just can’t deliver information the same way that a well-timed quip or a profound observation by a character can.

In contrast to dialogue, a monologue is a single, usually lengthy passage spoken by one character. Monologues are often part of plays.

The character may be speaking directly to the reader or viewer, or they could be speaking to one or more other characters. The defining characteristic of a monologue is that it’s one character’s moment in the spotlight to express their thoughts, ideas, and/or perspective.

Often, a character’s private thoughts are delivered via monologue. If you’re familiar with the term internal monologue, it’s referring to this. An internal monologue is the voice an individual (though not all individuals) “hears” in their head as they talk themselves through their daily activities. Your story might include one or more characters’ inner monologues in addition to their dialogue. Just like “hearing” a character’s words through dialogue, hearing their thoughts through a monologue can make a character more relatable, increasing a reader’s emotional investment in their story arc.

There are two broad types of dialogue writers employ in their work: inner and outer dialogue.

Inner dialogue is the dialogue a character has inside their head. This inner dialogue can be a monologue. In most cases, inner dialogue is not marked by quotation marks. Some authors mark inner dialogue by italicizing it.

Outer dialogue is dialogue that happens externally, often between two or more characters. This is the dialogue that goes inside quotation marks.

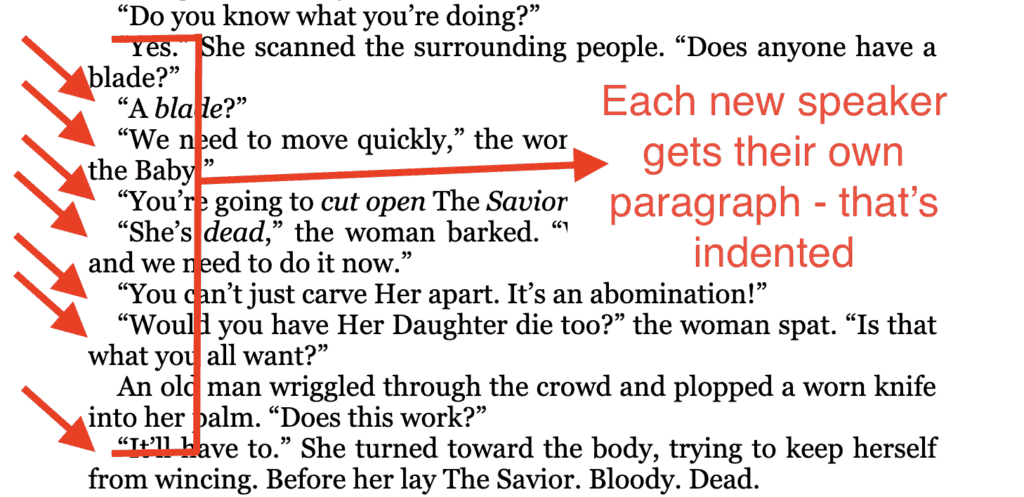

Give each character a unique voice (and keep them consistent)

If there is more than one character with a speaking role in your work, give each a unique voice. You can do this by varying their vocabulary, their speech’s pace and rhythm, and the way they tend to react to dialogue.

Keep each character’s voice consistent throughout the story by continuing to write them in the style you established. When you go back and proofread your work, check to make sure each character’s voice remains consistent—or, if it changed because of a perspective-shifting event in the story, make sure that this change fits into the narrative and makes sense. One way to do this is to read your dialogue aloud and listen to it. If something sounds off, revise it.

As I stepped onto the bus, I had to ask myself: why was I going to the amusement park today, and not my graduation ceremony?

He thought to himself, this must be what paradise looks like.

“Mom, can I have a quarter so I can buy a gumball?”

Without skipping a beat, she responded, “I’ve dreamed of working here my whole life.”

“Ren, are you planning on stopping by the barbecue?”

“No, I’m not,” Ren answered. “I’ll catch you next time.”

Here’s a tip: Grammarly’s Citation Generator ensures your essays have flawless citations and no plagiarism. Try it for citing dialogue in Chicago, MLA, and APA styles.

Dialogue is the text that represents the spoken word.

Write better dialogue in 8 minutes.

How to write a dialogue?

The dialogue that is written, should be composed in such a way that it appears to be spontaneous and natural, and a free-flowing conversation. The writer of the dialogue has to put himself/herself into two imaginary persons so as to make them express their opinions as two different persons in a natural way.

Can you write a book without dialogue?

Taught by a Bestselling Author with YEARS of experience doing JUST THIS! Learn the most recent fiction marketing tactics, Amazon algorithm deep-dive, with case studies, & more. You can’t write a book without dialogue—and you can’t write a good book without good dialogue (even if you’re writing a nonfiction book !).

Why is a dialogue better than a narration?

Having dialogues along with stage directions instead of just narrations can be said to be a better writing technique as it gives the readers a clear picture of the characteristics of the various characters in the story, play or movie. It also gives your characters life, and above all, a voice of their own.