As a business owner or accounting professional, you’ve likely encountered the term “bad debt expense” before. But what exactly is it and how do you record it in your books? This article will explain bad debt expense provide journal entry examples, and give you tips on how to account for it properly.

What is Bad Debt Expense?

Bad debt expense refers to accounts receivable that are deemed uncollectible. It represents money that is owed to a company by customers who have defaulted on their payments.

For example, let’s say Company XYZ sells $100,000 worth of product to Customer ABC on credit. Customer ABC takes possession of the inventory but is unable to pay off the amount owed. After multiple failed attempts at collection, Company XYZ determines they will not be able to collect the accounts receivable balance. The $100,000 is now considered bad debt expense.

Bad debt is an inevitable part of doing business on credit. While processes can be implemented to minimize default risk, no company can completely prevent bad debt. Accounting for estimated losses from bad debt allows a business to anticipate write-offs and report accurate net income.

Common Ways to Record Bad Debt Expense

There are two primary methods for recording bad debt expense:

1. The Direct Write-Off Method

Under this method, bad debt expense is not recorded until an account is specifically identified as uncollectible and written off.

The direct write-off method is easier from an accounting perspective. However, the main downside is it can result in an overstatement of net accounts receivable and net income in the period the sale was made.

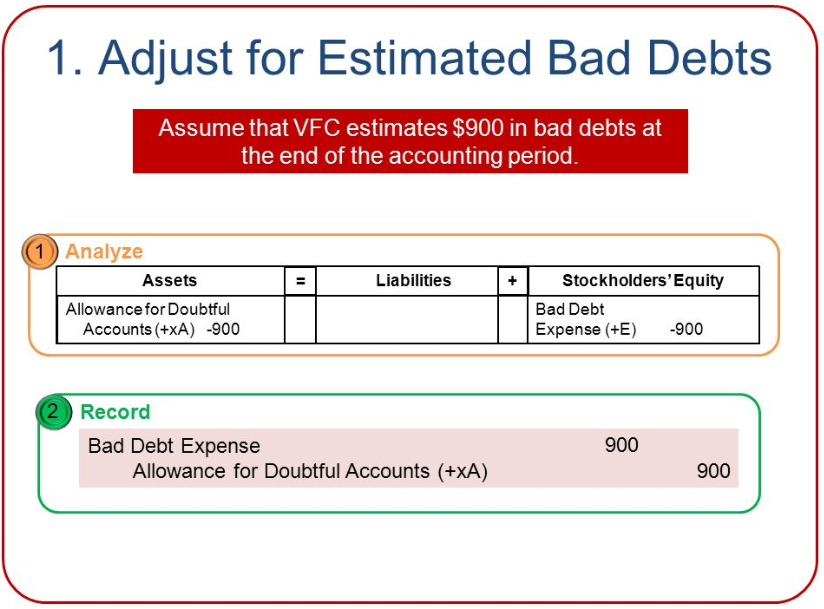

2. The Allowance Method

The allowance method records estimated bad debt expense at the end of each period. This is achieved by making an adjusting entry that debits bad debt expense and credits allowance for doubtful accounts. The allowance account is netted against accounts receivable on the balance sheet.

The allowance method better adheres to the matching principle and presents a more accurate picture of accounts receivable. However, it does require effort to estimate future write-offs.

Bad Debt Journal Entry Examples

Let’s look at some example journal entries for recording bad debt expense under each method.

Direct Write-Off Method

- Write-off of accounts receivable previously recorded:

<pre>Bad Debt Expense $100,000 Accounts Receivable $100,000</pre>

- Write-off of accounts receivable in same period as sale:

<pre> Accounts Receivable $100,000 Sales $100,000 Bad Debt Expense $100,000 Accounts Receivable $100,000</pre>

Allowance Method

- Estimated bad debt at 5% of net credit sales:

<pre> Bad Debt Expense $5,000 Allowance for Doubtful Accounts $5,000 </pre>

- Write-off of uncollectible accounts receivable:

<pre> Allowance for Doubtful Accounts $2,000 Accounts Receivable $2,000</pre>

- Recovery of accounts previously written off:

<pre> Cash $1,000 Allowance for Doubtful Accounts $1,000</pre>

Tips for Handling Bad Debts

-

Use historical data to estimate bad debt percentage

-

Review individual receivable balances and customer data

-

Write-off accounts after reasonable collection efforts

-

Follow up on old receivables frequently

-

Avoid extending additional credit to past due customers

-

Require deposits and prepayments for high-risk customers

Properly recording bad debt expense according to GAAP accounting standards takes some work. But accurately reflecting losses from uncollectible accounts will benefit your business in the long run. The key is finding a method that works for your unique situation.

Section How to Guess: The Income Statement Method

When calculating bad debt expense based on the Income Statement method, you will use a temporary account to determine a temporary account. This method is the easiest of the two methods. First, you are given a management estimate of the percentage of credit sales that are expected to be uncollectible, e.g., 2%. To calculate the bad debt expense, simply take the net credit sales from the period and multiply it by the given percentage. Sales is a temporary account, and when multiplied by the stated percentage, a temporary account is the result: bad debt expense.

A basic example is provided below:

| 600,000 | * | 0.02 | = | 12,000 |

| Net Credit Sales | * | Percentage | = | Bad Debt Expense |

| Bad Debt Expense | 12,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 12,000 |

As you can see, this is a very basic example. One way that it could be more complicated is by requiring you to calculate net credit sales. Net credit sales is calculated as total credit sales less discounts, returns, and allowances.

| Total Credit Sales |

| (Returns) |

| (Discounts and Allowances) |

| Net Credit Sales |

In the following example In the following example, you are given gross credit sales instead of net.

| Total Credit Sales | 600,000 |

| (Returns) | (40,000) |

| (Discounts and Allowances) | (10,000) |

| Net Credit Sales | 550,000 |

| 550,000 | * | 0.02 | = | 11,000 |

| Net Credit Sales | * | Percentage | = | Bad Debt Expense |

| Bad Debt Expense | 11,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 11,000 |

That’s about as hard as the Income Statement method can get. All you have to do is multiply the net credit sales by the given percentage and the result is the bad debt expense. Pause for a second and think about why we are multiplying by net credit sales instead net sales?>

Consider this: an account cannot be uncollectible if the customer paid cash, right? Because the account has already been collected! So if we multiplied the uncollectible percentage by net sales instead of net credit sales, weve included sales that have already been collected, namely, cash sales.

Now extend that logic to the following question: why net credit sales instead of gross credit sales? Why are we subtracting returns and discounts and allowances? In this whole process, what we are trying to do is determine how much of the money that we are rightfully owed is not going to be paid. Are we owed money from customers who return the merchandise? Nope. And if we give a 10% discount, are we owed that 10%? Nope. So if we were to include returns or discounts and allowances in our calculation, that wouldnt make any sense at all.

Now that youve mastered the Income Statement method, lets look at the Balance Sheet method. Its slightly more complicated, involving an extra step.

Section I An Allowance

If we know that some accounts are not going to be collected, we can’t rightly present the Accounts Receivable account at full value on the Balance Sheet, because we don’t actually think we are going to be able to collect all of those accounts. We would be presenting our most hopeful value, which isn’t conservative, so we need to present the value that we actually think we are going to be able to collect. This is called the net realizable value.

We can’t mess with the Accounts Receivable account directly because we don’t know which accounts are going to go bad (i.e., be uncollectible), we just know that some are. So rather than directly adjust some of the accounts, we are going to have an allowance that reduces the total value of the Accounts Receivable account. The Allowance for Bad Debts account is that account.

Allowance for Bad Debt is a contra-asset whose only purpose is to bring the Accounts Receivable account down to the reportable net realizable value. (Note, that like bad debts, the Allowance for Bad Debt has multiple names, including Allowance for Uncollectible accounts and Allowance for Doubtful accounts. They all mean the same thing and can be used interchangeably.) That gives us the following formula:

| Accounts Receivable |

| (Allowance for Bad Debt) |

| Net Realizable Value |

We now know the purpose and usage of both the Allowance for Bad Debt account and bad debt expense, but how do these two accounts actually work together?

Think of a mandatory savings account where you are required to put in a certain amount each month: you deposit, deposit, deposit, and eventually an event comes along where you withdrawal some of that money you’ve been storing up.

This is symbolic of the relationship between bad debt expenses and the Allowance for Bad Debt. Every period we must recognize an expense because we know that eventually some accounts are going to go bad. We don’t know when or for how much, but we believe it’s coming and are therefore required to recognize an expense. So we recognize the expense and then what? No account has gone bad yet, but we’re ready just in case one does. We increase our “savings account,” the Allowance for Bad Debt. (Note that this is a metaphor, we are not actually setting aside cash.)

We store it up until an account actually does go bad, in which case we are ready, no further expense necessary! We’ve already expensed all we needed to. Consider the name of the account: “Allowance for Bad Debt.” Its the perfect logical name: We are allowing for the case when an account becomes uncollectible, i.e., a bad debt. Hence: Allowance for Bad Debt.

With the big picture in mind, let’s get down to the actual accounting details: the journal entries.

Accounting for Bad Debts (Journal Entries) – Direct Write-off vs. Allowance

How to make journal entry for bad debt expense?

Hence, making journal entry of bad debt expense this way conforms with the matching principle of accounting. Under the direct write-off method, the company records the journal entry for bad debt expense by debiting bad debt expense and crediting accounts receivable.

What is a bad debt expense?

What is Bad Debt? The Bad Debt Expense is a company’s outstanding receivables that were determined to be uncollectible and are thereby treated as a write-off on its balance sheet. What is the Bad Debt Expense in Accounting?

How do you write off a bad debt expense journal?

Input the total lost payment amount in both the allowance for doubtful debts and accounts receivable sections. For example, if a customer owes $1,000 and the company concludes they can’t collect the debt, then the write-off entry would look like this: Here are a couple of examples of bad debt expense journal entries:

What is a bad debt journal entry?

A bad debt journal entry is part of the necessary adjusting entries in accounting. The US GAAP requires businesses to recognize bad debt expense in the same period as the revenue that generated it. Recognizing bad debts promotes conservatism in the financial statements because it reports A/R at its net realizable value.